When something really worries me, I try to channel that anxiety into action, focussing on ways to improve the situation even a little bit. As European leaders backtrack over themselves to congratulate Donald Trump, I hope they too are seeking to channel their anxiety over the future of European security into action of a more substantive and substantial kind. After all, Europe, a wealthy, industrialised continent, should be capable of safeguarding itself. Its security should not be left to the discretion of a U.S. leader thousands of miles away.

Inflatable Uncle Sam astride a missile, 4th July 2022, USA.

Europe has had years of warnings to take its security seriously, yet it has failed to respond with sufficient action. Keir Giles’s book Who Will Defend Europe? tackles this question directly, examining which countries are falling short and which ones could provide models for others to follow.

While there are clear differences between European nations, a troubling trend emerges to various degrees: an ongoing failure to mobilise society, industry and government to confront the region’s security challenges. To my mind, this reflects a broader crisis of ownership (broadly understood) across European democracies, where both citizens and governments feel detached from responsibility and accountability, constrained by the influence of impersonal institutions and distant elites.

This “crisis of ownership” is at the root of Europe’s inaction and I understand it as falling in four main categories:

1. Economic and Political Ownership

• Resource Control: Europe must take control of its own defence resources and build the political and economic capacity to secure them, instead of relying on American support. This involves not only funding its own security but also ensuring that it has the infrastructure and capabilities to respond to crises independently and affordably. Yet in recent years, Europe has allowed critical resources and strategic assets to fall into the hands of foreign entities with interests contrary to Europe’s own. For example, the UK, once a global leader in steel production, sold much of its steel industry to China, In another example, Russian oligarchs have acquired properties near sensitive military installations across Europe.

2. Personal Responsibility and Accountability

• Owning Actions: Europe’s leaders need to take responsibility for their own defence, owning the decisions and costs involved rather than relying on another nation. “Owning” its defence means taking concrete actions, not simply pledging support or making symbolic gestures. Europe’s repeated delays in providing promised military support to Ukraine (think ammunition) reflects this a hesitation to assume full accountability, and signals an unreliable commitment to defence (not true of all countries but collectively).

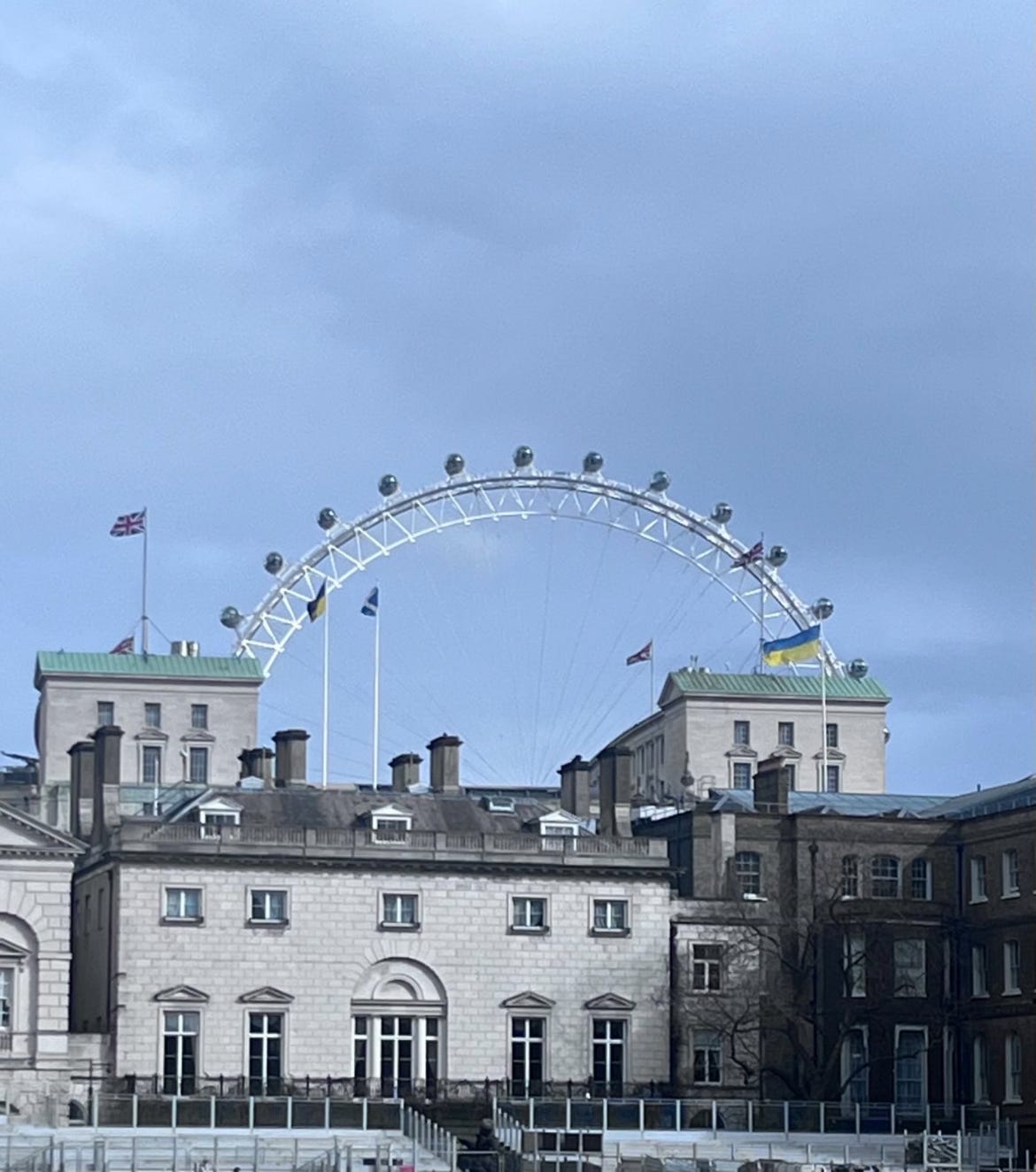

The Ukrainian flag flying over Downing Street, 2024. Flags are nice but timely Storm Shadow deliveries are nicer.

This lack of accountability is felt in many ways, most of them beyond my purview, but specifically to Ukraine and Russia, I wonder where is the accountability for the UK and US signing the Budapest memorandum? Where is the accountability or recognition of London’s failed policy of engaging and indulging Russian elites to gain leverage over Putin? Where is the accountability for talking all the talk, but then not walking the walk? Luke Harding and Dan Sabbagh wrote on this in relation to recent strains in the U.K.-Ukraine relationship.

3. Emotional and Psychological Ownership

• Sense of Belonging: Emotional and psychological ownership of Europeans’ responsibility for the future of their continent is essential to fostering a stronger commitment to shared security. Yet, in many parts of Western Europe, the sense of collective responsibility for security has been weak. The disconnect is stark when compared to Eastern European countries, where people see Ukraine’s fight as directly linked to their own future and interests. This complacency reflects more than just a deep detachment from the principles of solidarity, it also reflects a smug sense of ingrained privilege in some Western European countries that they are real Europe and that Ukraine is a peripheral country, separate and separable from them and their interests.

Polish information campaign, Warsaw 2022. It reads ‘High energy prices are also his [Putin’s] weapon’

4. Social and Cultural Ownership

• Collective Responsibility: Europe needs a unified approach to security, one that reflects shared ownership of its defence and an acknowledgment of mutual responsibility for regional stability. Yet, European openness to foreign influence—meant to safeguard freedom and transparency—is often simply a lack of intervention. Europe’s regulatory framework, designed to protect liberties, is now frequently exploited to undermine them. Russia does not present an alternative system to Europe’s so much as a subversion of the system in the interests of the regime and state. The playbook of rules that are supposed to ensure freedom and decency is broken, used back against itself, yet nobody seems to truly grasp that the problem lies in the redundancy of the so-called ‘liberal international order’, which never really existed except as a global projection of America and its allies’ interests after 1991.

This lack of introspection on why liberal democracies are struggling to rise to many of the challenges of the age (although I would add that liberal democracy is to my mind still a far better option than any other) sees many European countries spend vast sums on consultants tasked to impose its theories of stabilisation and cohesion abroad, presenting them as an unassailable model for other countries, even those that face more pressing security concerns.

Many European leaders act as if the liberal frameworks created in their own unique contexts—and selectively applied at home—are universally ideal and should guide “lesser” countries. They remain committed to this view even when it is clear that Europe’s openness has been weaponized against it. When the facts changed, John Maynard Keynes famously changed his mind. European leaders, however, seem unwilling to adapt in the face of shifting threats. They hold to their frameworks as gospel, appearing to lack not only in Keynes’ adaptability but also his commitment, and sense of vision. This ideological rigidity only deepens Europe’s vulnerability, blinding it to the urgent need for more robust, protective measures that align with the new security realities.

For decades, Europe has relied on the U.S. as its security guarantor, assuming that NATO would always offer protection. This expectation has allowed Europe to defer responsibility for its own defence, treating American support as a given. But expecting the U.S. to continue covering Europe’s defence indefinitely is unsustainable, unjustifiable, unreasonable and very unlikely now.

Trump’s insistence that Europe shoulder more of its own defence costs is a reasonable demand. The reality is that European countries have relied on America to underwrite their security for far too long. The reluctance to invest sufficiently in defence forces and infrastructure has left Europe unprepared to confront challenges like Russia’s aggression in Ukraine, placing undue burden on the U.S. and diminishing Europe’s credibility as a serious security partner.

Pro-Trump stand in liberal California, 2022.

Ideological underpinnings of incompetence

This lack of commitment also reflects a broader ideological shortfall. Europe’s hesitation to fully support Ukraine’s and its own defence stems from what we might call a “teleological liberalism”—a belief that liberal democracy will inevitably prevail without active effort. This kind of complacency has proven dangerous. Europe’s reliance on the idea that peace will maintain itself or somehow a fudge peace will emerge has led to insufficient action, leaving it vulnerable to the threat posed by Russia, which is not spending 40% of its GDP on defence, militarising its children, and shifting to a war economy in anticipation of pursuing peaceful objectives in the short, medium or even long term.

The question of European defence is no longer just a matter of budget targets or meeting NATO spending commitments. It requires a fundamental reassessment of Europe’s security priorities, one that reflects a genuine commitment to independence and resilience. Europe must recognise that Ukraine’s fight is also its own and that defending its future demands more than relying on an ally’s goodwill.

Taking real ownership means Europe must be willing to invest in its own defence, strengthen its military capabilities, and build a cohesive strategy that ensures its security does not rest on the unpredictable policies of any one American administration. Failure to do so will deepen Europe’s vulnerabilities and leave it exposed to adversaries in a rapidly changing world. Ironically, successfully meeting this challenge is also probably the most likely way to maintain a serious level of US support under President Trump.

Fundraiser:

As discussions of a peace deal grow, I worry for those Ukrainians left in the occupied territories, probably feeling hopeless and forgotten, and likely struggling to find the money to leave. Helping to Leave provides free evacuations and then ongoing support to refugees from the frontline zones and from inside the occupied territories. Please help them if you can:

https://helpingtoleave.org/en#donate