Collaboration?

Every war has its collaborators—whether motivated by ideology, identity, financial incentives, resentment, personal grievances, or sheer survival. Ukraine is no exception. However, the topic of collaboration is highly politicised, particularly in Ukraine’s context, where the aggressor—Russia—has fabricated a false pretext claiming that southern and eastern Ukraine desired to be invaded and have their homes and lives destroyed. Ironically, it is by examining collaboration and its drivers in greater depth that the falsity of Russia’s pretext becomes even clearer.

The starting point for any discussion of collaborators, particularly for Westerners and Russians, must be the statement by British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden during the Second World War: “No country that has not been occupied can judge one that was.”

There is a profound difficulty in understanding the choices individuals make under the pressures of occupation. The moral ambiguity and complex realities of collaboration resist simplistic categorisation. Moreover, while collaboration does occur, it must be viewed against the backdrop of the horrific conditions in occupied territories—far more repressive than conditions within Russia itself—the ongoing and effective resistance movement, which has no parallel within Russia, and the immense scale of settler colonialism imposed by Russia, which introduces an additional layer of helpless despondency.

An abandoned village north of Kharkiv, a few kms from the frontline

Collaboration: A Problematic Concept

All that said, the issue lies as much in the general definition of what is collaboration as in the way it is applied: collaborationism is a term that implies betrayal, suggesting a clear line between loyalty and treachery. But such a clear line seldom exists. In practice, collaborationism encompasses a wide range of behaviours, from active support for occupying forces to the minimal compliance required for survival. This ambiguity makes it a deeply fraught concept.

The broad definitions of collaboration in Ukrainian law mirror historical precedents, such as those seen in post-Second World War France. After liberation, France prosecuted over 120,000 individuals for collaboration with the Nazi occupiers. These prosecutions ranged from serious crimes, like joining the German military, to far less egregious actions, such as continuing to run a business that served German customers. Similar risks exist in Ukraine, where laws criminalising political, economic, and cultural collaboration may ensnare individuals whose actions were coerced or driven by survival, rather than ideology.

This legal ambiguity is compounded by the impossibility of fully understanding the choices individuals make under occupation. For example, accepting a Russian passport in an occupied Ukrainian territory might be viewed as a betrayal. Certainly, some Ukrainian officials have suggested as much, yet others, such as Tamila Tasheva, have been clear that it is not, and Ukrainian law does not recognise Russian passports taken under duress.

For the vast majority of people in the occupied territories, accepting a Russian passport is a necessity to access healthcare, pensions, or other basic services controlled by the occupying authorities. It is also often the only way to leave the occupied territories. Some Ukrainians in free Ukraine but involved in clandestine evacuations have spoken of the immense moral burden they bear: they cannot advise those seeking to leave occupation to take a Russian passport without potentially causing problems for their organisation and efforts, yet doing so is often the best course for those who wish to escape.

Similarly, many engaged in non-violent resistance would be safer taking a Russian passport, as it makes them less suspicious to occupation officials who generally fail to distinguish between violent and non-violent resistance (a distinction that, regrettably, exists largely in the minds of Western funders rather than the torturers). However, even that is not enough of course. For example, the (legitimate and exiled) mayor of Mariupol, Petro Andryushchenko recently covered the story of a resident of Mariupol, who accepted a Russian passport, and then was later arrested by the FSB for donating to the Ukrainian Armed Forces and promoting resistance. This individual exemplifies the moral ambiguity of life under occupation—using a passport for survival while simultaneously trying to support Ukraine.

One of the most significant forces driving collaboration is existential and financial necessity. What Russians call ‘liberation’ is more accurately described as total destruction, leading to economic collapse and leaving residents with few options for survival. Many do not have the money needed to leave—whether for bus, train, or plane tickets—or to establish themselves in Ukraine. While support services are available, these come with their own challenges, which I will explore in another post on the issues internally displaced persons (IDPs) face. Others may not want to leave their homes or are unable to due to caregiving responsibilities.

In Russian-controlled areas of Ukraine, occupation authorities offer employment and resources that might otherwise be inaccessible, creating a stark choice between destitution and compliance. In practice, residents often have little choice and are pressured into working for Russian-installed administrations to secure access to food, water, or medical supplies.

At the other end of the spectrum, and from my own experience, I know how, in frontline areas, individuals engage in actions ranging from spraying over Ukrainian tridents to marking targets for Russian forces or sabotaging Ukrainian infrastructure, often in exchange for payment. These activities have increased recently as Russia has refined and expanded its information and psychological operations (IPSO). Green military vehicles are frequently burned in exchange for $1,000. Coordinates are provided for cash or cryptocurrency.

Crossed out Ukrainian tridents in a frontline city (in free Ukraine).

While some of these individuals may be pro-Russian, many are simply cynics. Actual pro-Russians are overwhelmingly apathetic. Fittingly, many of the pro-Russian neighbours or individuals I know of tend to be over 45, watching Solovyov on their laptops, and disciplined only in their inaction. They are full of spite, unhappy, disconnected from reality, and utterly incapable of taking meaningful action beyond waiting for someone else to come and fix their problems. In other words, they are identical to the very Russian society for which they hold such fondness.

A Question of Political Choice

A persistent misconception is the belief that collaboration is tied to ethnic identity, particularly to the so-called “Russian ethnic minority” in Ukraine. This framing is both misleading and unhelpful. As I have written before, I do not believe there is a Russian ethnic minority in Ukraine in the way many Westerners understand and use the term.

First, the term ethnic minority is laden with certain connotations. For a British or Irish audience, referring to a Russian ethnic minority in this context is akin to referring to a British ethnic minority in Northern Ireland during the 1970s. It is crucial to understand why the British were there in the first place and to consider the power structures that complicate Western assumptions about ethnic minorities—typically seen as groups deprived of power due to structural inequalities linked to their minority status. Second, in a post-imperial context between two neighbouring countries, identity in such circumstances is not a fixed attribute but often a political or ideological choice.

Take, for instance, General Oleksandr Syrskii, the Ukrainian Commander in Chief born in Russia to Russian parents. According to the logic of ethnic categorisation, he could be considered part of a Russian minority. Yet he isn’t. Similarly, would someone with an Irish surname and partial Irish heritage living in Britain be considered part of an Irish ethnic minority? In such contexts, identity often becomes a matter of personal and political decision rather than an immutable fact. Being a Russian speaker does not make you part of a Russian ethnic minority—an ultimately Western construct that doesn’t fit Ukraine’s reality. Just ask Azov. Or Kraken. Or Bratstvo. Or, if you are feeling particularly brave, try calling an Irishman in Dublin an English minority because he speaks English.

Izyum is rebuilding. Other towns in Kharkiv oblast are beyond repair.

That said, empire has left its mark. We see this in border towns like Kupiansk and Vovchansk (or rather, we did see it; Vovchansk has now been wiped off the map). Many villages around these towns were populated by people who lived off border trade or had come decades ago to work in factories staffed from across the Soviet Union. Consequently, these areas had more residents who either never saw a difference between Russia and Ukraine or who chose not to see one because it didn’t align with their economic interests or personal narratives.

In villages near the Russian border with such demographics, younger residents—those who had lived their entire conscious lives in an independent Ukraine—were often shocked at how readily some older residents accepted Russian-installed authorities.

This, of course, tells us little about their motives. Perhaps they see collaboration as an inevitable choice given their circumstances. Perhaps they simply don’t care. Perhaps they have always harboured resentment towards Ukraine. We cannot always understand what drives others—or even what drives ourselves. But such decisions are rarely reducible to identity or inherent traits.

Consider the story of a man I know from Donbas. In 2014, he joined the Ukrainian resistance. According to him, he and his group of partisans were betrayed to the gangsters and Russians by people originally sponsored by a well-known Ukrainian oligarch from the region. This man, a Russian-speaking Ukrainian with roots across the Soviet Union, was then brutally tortured for weeks. His torturers? Pro-Russian communists from Lviv—a city traditionally associated with Ukrainian nationalism.

Collaboration is not inherently tied to ethnicity or language but arises from political choices shaped by ideology, history, and circumstance. Acknowledging this and trying to find a practical solution that helps Ukrainians, the government has implemented programmes like I Want to Go to My People (Хочу к своим), which offer convicted collaborators the chance to defect to Russia in exchange for Russia releasing Ukrainian civilians it has imprisoned. However, Russia rarely wants its collaborators, shrewdly viewing those who betray their own country as individuals likely to betray them as well.

Problems in Addressing Collaboration

Collaboration is such a complex and sensitive issue that addressing it effectively is almost impossible. Unsurprisingly, Ukraine’s system for managing collaboration suffers from significant shortcomings, many of which stem from fragmented leadership, conflicting priorities, and a lack of coordination among institutions. These systemic problems, combined with vague laws and inconsistent enforcement, have resulted in an uneven and often flawed approach to tackling collaborationism.

One major issue lies in the vagueness of Ukraine’s collaboration laws. Initially focused on military collaboration following the annexation of Crimea in 2014, these laws have since been expanded to cover political, economic, and cultural activities. However, the definitions remain overly broad and poorly delineated, making it difficult to distinguish between coerced actions and voluntary betrayal. This ambiguity frequently leads to unfair prosecutions, overwhelming the judicial system—particularly in frontline and liberated areas—and fuelling resentment among affected populations.

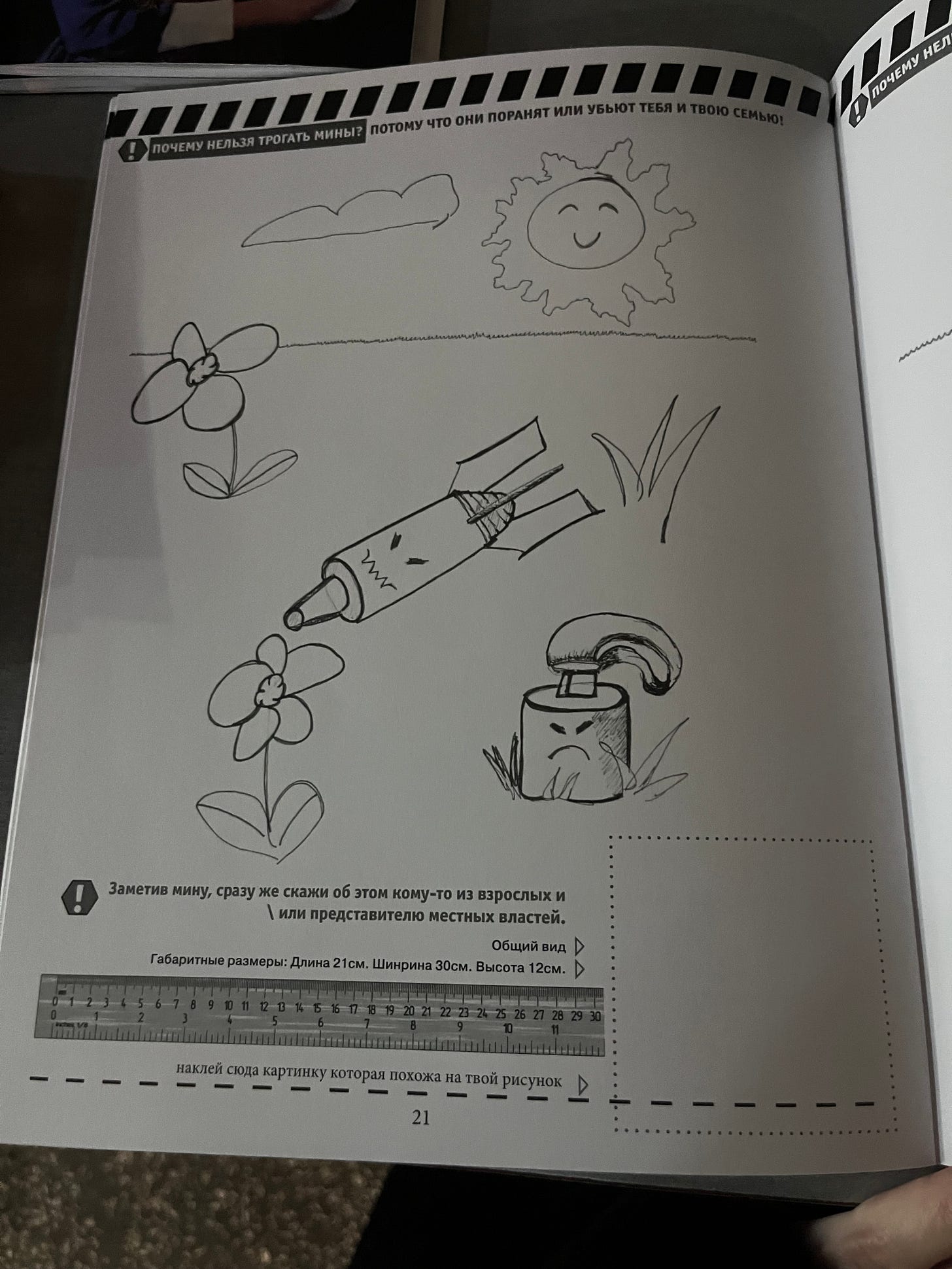

Inserts from a colouring book for children teaching them of the dangers of mines and weapons. It is given out in Donbas, photo taken not far from Slavyansk.

Coordination challenges within Ukraine’s security sector further exacerbate these issues. The Security Service of Ukraine (SBU), Ministry of Defence, Ministry of Justice, Armed Forces of Ukraine (AFU), and local authorities often operate on similar issues without clearly defined roles or responsibilities.

These challenges have been compounded by the dissolution of the Ministry for Reintegration of Temporarily Occupied Territories. For all its leadership flaws and the unhelpful statements of Minister Vereshchuk, this body at least provided centralised leadership on reintegration efforts. Its responsibilities have now been redistributed among the Office of the President, Cabinet of Ministers, and other agencies, resulting in greater fragmentation and inefficiency. On Tuesday, it was announced that a new institution, the Ministry for Ukrainian Unity, would take its place. It remains unclear how this new body will differ from or continue the work of its predecessor.

Local IDP councils and ad hoc bodies have been left to fill the gaps. However, these councils face significant financial challenges, with no funding provided by either the Ukrainian government or Western donors. Many have already closed due to a complete lack of resources, while others rely solely on word of mouth to advertise their services. They struggle to host meetings because they cannot afford basic costs such as printing, let alone rent premises. This leaves displaced populations from occupied areas without critical support networks or knowledge of their rights. For example, IDPs are entitled to the same benefits and rights as any other resident in their locality, yet many remain unaware of these entitlements.

Given the hundreds of millions spent by Western governments on “building resilience in Ukraine,” it is scandalous that no money has been allocated to these councils, which provide vital support to highly vulnerable groups. This situation highlights the arrogance at the heart of the international development industry. While a thousand pointless workshops bloom in western Ukraine, the lack of real action in eastern Ukraine has led to a troubling phenomenon: the return to occupied territories. The challenges faced by displaced populations, coupled with the gaps in support systems, have left some IDPs feeling they have no choice but to return to their homes, even under occupation.

Although the exact numbers are difficult to ascertain, anecdotal evidence suggests the trend is significant enough to raise concern. Efforts to gather accurate figures must, however, be approached cautiously. For instance, in Mariupol, the mayor wrote of estimated 30,000 to 40,000 “nomads” temporarily returning in 2024, often to re-register property or meet bureaucratic requirements imposed by occupation authorities, before returning to Ukrainian-controlled areas. Similarly, many returnees were initially deported to Russia.

Yet there are also verified cases of individuals returning from free Ukraine out of perceived necessity, unable to secure stable housing or employment in Ukrainian-controlled areas. These dynamics underscore the socio-economic pressures that compel returnees, even when the risks of occupation are clear. Still others choose not to evacuate impending occupation because they fear the grim conditions of temporary accommodation. Reports abound of IDPs sent to drab student hostels where they are banned from showering outside of designated hours or receive inadequate support. For many, remaining in their own home—despite the dangers—feels preferable to such conditions.

It is baffling that these circumstances persist, given the significant sums Western governments allocate to resilience and humanitarian aid. Hostels designated for displaced persons have received international funding, with many renovated using these grants. So where are the on-the-ground monitors ensuring that service providers deliver on what they were funded for? The issue here is not one of Ukrainian corruption but of Western incompetence—compounded by the all-too-familiar failure to remember that this money did not materialise from nowhere. It was taken from the taxes of citizens who would rightly expect these funds to reach the Ukrainians who genuinely need them.

Injustice

Compounding the challenges listed above are perceptions of selective justice. High-profile figures with connections to occupied territories often escape accountability, undermining public trust in the system. For instance, Ukrainian MP Roman Ivanisov received millions of hryvnias from his mother, who owns a factory in Russian-occupied Berdyansk. Despite these ties to the occupied region, Ivanisov has faced no serious repercussions, although following a journalistic investigation the prosecutors are now looking into the situation.

In Zaporizhzhia, someone has tried to etch in and restore the removed letters that originally spelled out a building’s Soviet era name.

Meanwhile, local institutions are struggling to manage the mounting workload. Judicial systems in frontline or deoccupied areas are overwhelmed by collaboration cases. Underfunded police forces and courts cannot process the volume of cases effectively, leading to delays and public frustration. Security agencies arguably also have a disproportionate influence over collaboration policies. The drafting of these laws has often prioritized national security over humanitarian and social considerations, creating a framework that emphasizes punishment rather than reconciliation. While totally understandable, this punitive focus risks alienating affected populations, particularly in areas where collaboration was coerced rather than voluntary.

Of course, it is all well and good criticising the law, but there has to be one. Some of those demanding the most punitive measures towards collaborators are those who lived under or fled occupation themselves but stayed true to Ukraine. Moreover, the broadness of the law means that not enough serious cases are prosecuted. When justice is delayed or inconsistently applied, there rises a risk of a resort to vigilantism. In Kharkiv region and the city itself frustration with judicial failures and the police has led to isolated incidents of people taking justice into their own hands, including killing known and active collaborators providing coordinates to the Russians. These actions, while rooted in genuine anger and rather inevitable in the circumstances, do not help Ukraine and risk only further undermining the rule of law and eroding public trust in the state’s ability to deliver justice.

Conclusion

The concept of collaborationism is fraught with ambiguity, encompassing a spectrum of behaviours that defy simple classification. In Ukraine, the pressures of occupation—economic necessity, coercion, and political manipulation—have blurred beyond distinction lines between survival and betrayal. Simplistic narratives and sweeping accusations fail to capture the complexities of these choices, risking alienation and division.

As Anthony Eden’s words remind us, judging the actions of those under occupation is a fraught exercise. Understanding collaboration requires empathy, nuance, and a willingness to grapple with the moral ambiguities of war. Only by examining these complexities can we begin to make sense of the difficult choices made in extraordinary circumstances.

That process begins by listening—to internally displaced persons (IDPs) and to those who have lived under occupation. Ukraine’s fragmented and inconsistent approach to managing collaborationism reflects broader institutional challenges and the inherent difficulty of balancing justice, security, and reintegration during wartime. But the solution is not to criticise the Ukrainian government, which, bluntly, lacks both the time and the resources to address these issues comprehensively. Instead, the responsibility lies more with Western donors and international development organisations. The decision-making bodies of such entities often apply superficial frameworks to understanding Ukrainian society and refuse to engage meaningfully with—or even visit—the areas they claim to be helping.

People often criticise academics for merely describing problems without offering solutions. Fair enough. But it is far better to describe a problem accurately than to offer solutions based on no understanding of the issue, or desire to listen to local partners who do understand.

More study and understanding are needed to create real justice—to punish those who freely choose to enable Russia’s destruction of Ukraine and Ukrainians, and for the victims of Russian coercion forced into actions for their survival, as well as protections for people whose views are morally repugnant to many but are not actively doing harm by listening to Solovyov in their apartments. This principle applies not only to Ukraine’s approach to collaborators but also to the international community’s approach to Ukraine, which is fighting an enemy that has deliberately sought to destroy it from both outside and within for decades.

Fundraiser

My friends at CodeIT for Ukraine have established a number of wonderful children’s play rooms across Kharkiv region, many of which largely cater to IDP children. Please see details of their fundraiser below:

Raising $25K for the expansion of the existing "kids room" in the town of Dergachi - They have already built four rooms here, although one has been destroyed by the invaders. I have a visited a few times, it is a very fun space and great for children who do not go to school and desperately need social interaction with their peers

Paypal link: https://www.paypal.com/donate/?hosted_button_id=JVRXMKKN5SVDN

The outside of the building in which the children’s rooms are located (image taken BEFORE the Russians again hit the building and destroyed one of the children’s rooms). An image of the inside of the children’s rooms (in the basement) is below