Betrayal

Last night the Russians hit a nine storey residential building in Saltivka, a working class dormitory region of Kharkiv. One child is dead. Another was trapped under the rubble at the time of writing. Rescuers have reported that others are trapped there too. At least 21 are injured.

Winter has come to Kharkiv and it will be cold and bloody.

Two nights earlier, I was on a video call with a soldier from Kharkiv when the Russians hit Derzhprom. A beautiful Soviet modernist building, it stands like a silent sentinel on the prettier side of Freedom Square, the side with the tulips so carefully arranged in springtime. When he told me, we both went silent.

Derzhprom

Derzhprom, with its bold architecture and towering presence, always evokes in me thoughts of the future. It rises above Freedom Square, until 1991 named Dzerzhinsky Square after the founder of the Soviet secret police. Now, another former leader of Moscow’s secret police haunts this square, drawing it into an ongoing struggle between its namesakes: terror and freedom.

Despite the ruined buildings all around it, Derzhprom always seemed to stand apart, projecting ideas grander than any present conflict. But now, even Derzhprom cannot stand aloof from the brutalities below. A building meant to evoke utopian dreams can no longer escape the weight of the present.

Kharkiv has retreated to its origins, as a fortress. A city of academics, inventors, physicists, and magnificent writers, will struggle to thrive as a fortress but such times concern survival, and survival only allows for core identities. Despite the constant waves of people arriving from the region, Fortress Kharkiv feels increasingly isolated. Original residents are leaving again. Many of those who left in the early months of 2022 but had since returned are once more packing their bags, fearful as winter approaches. And as the Russians approach.

In the region, in Kupiansk, Lyptsy and Vovchansk, the fighting rages and the Kharkiv fronts are delicate at best, struggling at worst. There isn’t much on the horizon that suggests it will get much better either.

Kupiansk in late summer 2024, during a relative lull in the fighting.

So it is no surprise that my conversations with friends and colleagues convey varying tones and shades of betrayal.

Some feel betrayed by the West. By the failure to uphold the Budapest Memorandum, by the failure to supply weapons on time, by the failure to provide the support it said it would, by its failure to understand the stakes for Ukraine and for Europe. When things are bad, the propagandistic state-run Telemarathon stokes these anti-Western sentiments, which helpfully deflect criticism from the government. Although given declining trust and viewership of the Telemarathon, I think most of this sense of betrayal is a raw common sense. I feel it too, but because I am from the group committing the betrayal, I feel it as shame. It is an understanding that the promises made to Ukraine - not only in 1994 - are to be broken. The West has given a lot of words, but not kept them.

OtherUkrainian friends feel a different kind of betrayal—not by the West, but by their parents’ generation for not building a better state when they had the chance, for not taking advantage of the opportunities they had. Many such people see this war as their final chance to do what is right, to secure a succesful Ukrainian state for the future.

Sometimes, they’re fiercely determined not to betray their children, whether or not they have any actual children. Sometimes, the older generation feels inspired by the young. I know two fathers who enlisted to follow their sons’ example. But generally, the under-25s are not on the frontlines as they are protected from mobilisation. This may seem odd but in the Ukrainian context it makes sense —there weren’t many of them to begin with, and Ukraine’s demographic nightmare would only deepen if they were lost.

The self-critical patriots do not blame the West for Ukraine’s struggle on the front, but they too feel betrayed by the West, albeit in a different way. It is more about broken dreams than broken promises. The news that North Korea was sending troops to Ukraine, and the West’s so far lacklustre response, has been interpreted as a final nail in the coffin, a sign that the West probably is as degraded and meaningless as Ukraine’s enemy presumed it would be.

Of course, the West isn’t the only actor betraying Ukrainians. At the start of the big war, those with connections and relatives in Russia felt betrayed by Russians. That doesn’t really come up anymore, at least in my conversations (but should not be read as forgiveness so much as contempt). Instead, people inevitably look for the enemies within. A common pain among my friends serving is that Ukraine’s best people are dying—the ones with a vision of a Ukraine worth fighting for, those who were supposed to build the country, not die at 26, or 37, or 33.

More than once someone has asked me, presumably not expecting an answer, ‘what is the point if the best of Ukraine dies?’ They want to know what type of people will be left behind and whether those people will build the Ukraine the heroes died for.

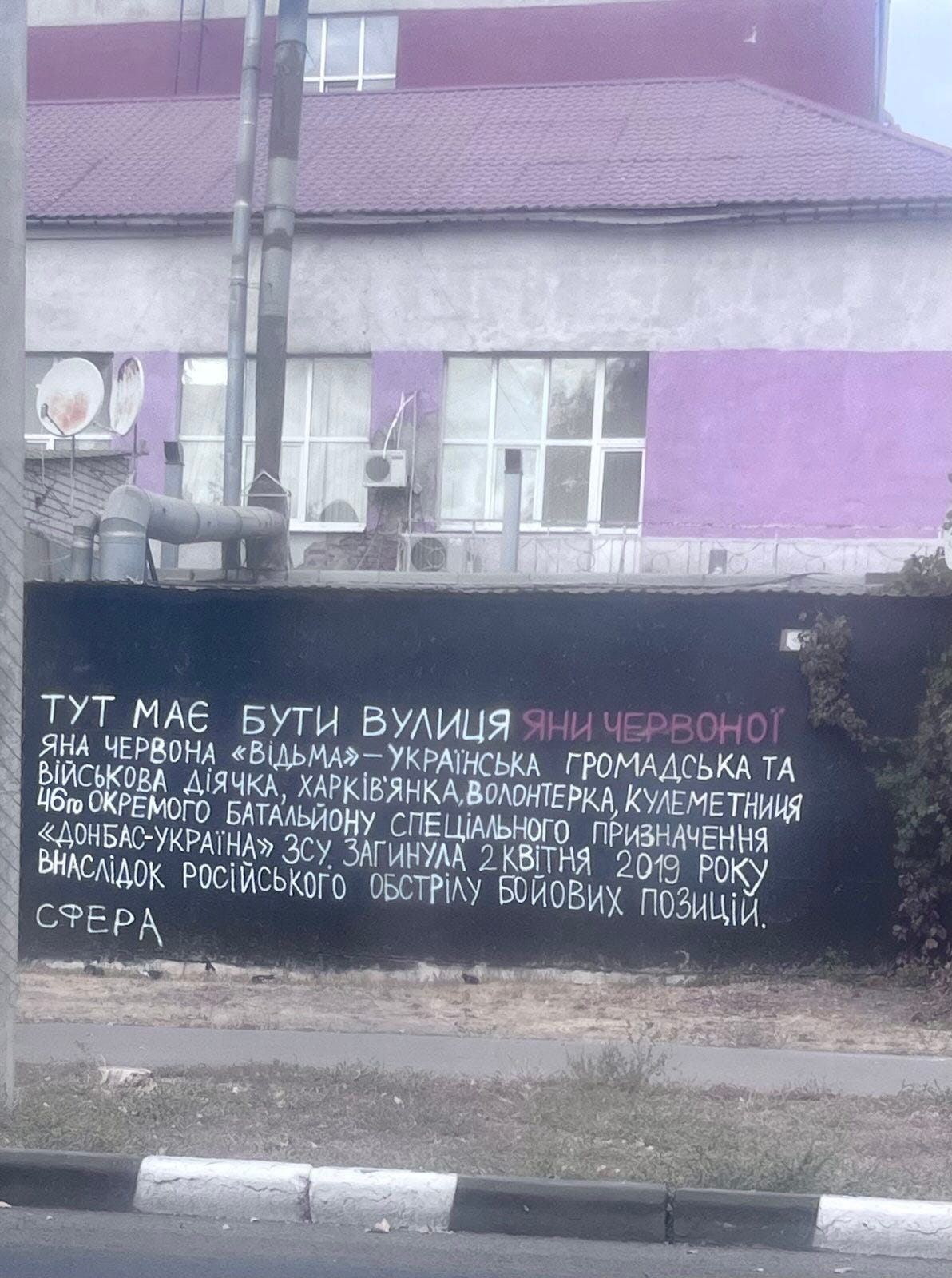

Graffiti on a street in Kharkiv. It reads: “This should be called Yana Chervona Street. Yana Chervona was a ‘witch’, an active figure in Ukrainian civil society and military, a Kharkivite, a volunteer, and a machine gunner with the UAF’s 46th separate special purpose batallion ‘Donbas is Ukraine’. She died on the 2nd May 2019 as a result of Russians shelling of [Ukrainian] military positions.

Tensions between civilians and the military are sometimes exaggerated, but there are frustrations. Often it is volunteers who get the short straw from both groups. In a recent conversation with a volunteer group evacuating people from frontline areas, I asked about their biggest challenge. I expected them to say that the system for assisting people wasn’t working. But the system is fine—the issue is that the same people keep calling for evacuation.

For example, back in May volunteers in Kharkiv repeatedly took calls from Vovchansk to evacuate the same elderly woman. The first time, they brought her to Kharkiv, set her up at the IDP base on Peace Avenue, where she received emergency funds, a new place to stay, food, and help to contact relatives. Then, two days later, the call comes in again for the same address. It was the same lady. A week later, the situation repeated itself all over again except that every time the guys went back, they were in more danger.

One elderly couple requested evacuation five times. They returned home because their neighbours, incorrectly, would tell them it’s safe. On one occasion in Lyptsy, the volunteers even had to evacuate a camel. Winning over the camel took hours, and by that time the owner—hitherto blind drunk —had sobered up and began accusing the volunteers of stealing his property, calling the police. Eventually, the camel was evacuated.

My own flawed expectations and the volunteers’ answer reminded me of a conversation with a soldier involved in the de-occupation process. I asked for his thoughts on how to smooth over civilian-military relations during liberation, making sure rights were protected and so on. He replied that soldiers need to feel safe, to know they won’t be ambushed by those they’re trying to protect. If soldiers feel secure, they’ll follow protocol, and fewer mistakes happen.

In that answer, there was so much insight—largely into the gulf between war as observed and war as experienced. In the West, civilians are the ultimate priority to be protected. But in Ukraine, it’s really the soldiers. Especially if you are a soldier. After all, just one rogue agent disguised as an ordinary civilian, especially in deoccupied areas, can pose a real threat. How do you know they won’t report on you? Or set your car on fire for a payout? There is a reason soldiers in Kharkiv don’t like to leave army (or khaki green) cars out overnight.

The social distance between the military/those with family in the military, and civilians is not large, but the current situation does not feel tenable. Coming from Kharkiv, it can feel surreal that life goes on so normally in many cities, especially Kyiv. One friend from a frontline city described it as ‘it is like everyone decided that the war was over and intended to live as if it were’. But I think it is just on the surface, when you look closer at the beautiful young woman in her immaculate clothes, you see a prematurely furrowed brow. When you watch, you see the confident man in a suit has a serious injury or nervous tic

The war is felt in different ways but everyone knows deep down it is far from over. A lot will change before that point is reached, both outside and inside Ukraine. Beyond the victory plan aimed at foreign audiences, the Office of the President has been discussing an internal victory plan to address the self-destructive tendencies common in all countries at war, but which have become more acute in Ukraine this year.

Some elements of this plan are already clear: dismissing the senior officials responsible for the military medical boards. It is to be hoped this means in the future no veterans have to bribe board members to receive the invalid status to which they’re entitled.

Last month, three Ukrainian deputies of dubious political and patriotic conviction were able to cross the border just before charges were brought against them, This made Prosecutor General Andrii Kostin’s dismissal somewhat inevitable. However, I would be surprised if responsibility truly lies with Kostin. Many Ukrainians I speak to feel deep disappointment with Zelensky and his team—a disappointment all the more painful because of the trust they had in him when he stayed in Ukraine during the full-scale invasion. They thought they’d finally found a leader worthy of their nation - and they had. But war and Ukrainian politics appear to take their toll even on the best of us.

For anyone interested in reading more about these issues, Bihus has the stories worth reading. The key point I want to convey is that, if you feel like pro-Russian politicians, whose families run successful businesses in occupied Berdyansk, have legal privileges that you, a law-abiding Ukrainian patriot, do not have, it is a recipe for trouble.

These matters only become more complicated when you get to the territories that were deoccupied. In Izyum, I met the father of a young man murdered in spring 2022, allegedly by former neighbours turned collaborators. Some of the suspects survived the occupation and resumed normal lives. The overloaded Izyum justice system couldn’t offer the father closure, so they insisted it was Russian forces who killed his son—it was simpler that way. The fishing shop where the young man worked has been renamed after him, and his father visits daily. Artur’s friends take care of the father, who carries bulging folders of documentation about his son’s murder everywhere he goes.

Artur’s fishing shop in Izyum, adorned with a photo of the murdered man.

It is good news that Zelensky recognises the need for an internal victory plan, and even better news that it will be developed in tandem with Ukrainian civil society. Because even if it is for a existential cause, it’s hard to keep fighting when justice feels betrayed on every side. It is important that betrayal does not become the final word of this war, although for many it is already a watchword. Ukrainians feel betrayed by the West; patriots feel betrayed by corruption; people under occupation feel betrayed that Ukraine didn’t return for them; those who’ve never lived under occupation feel betrayed by those who stayed under Russian control. In the parts of Donbas occupied in 2014, people seem to feel betrayed by both Russia and Ukraine, hating both and surviving out of spite. Even Russians have developed their own betrayal narrative: that Ukrainians betrayed them by aligning with the West and rejecting the Russian identity they wanted to impose.

Perhaps the only ones who don’t feel betrayed are the people of Western Europe, insulated by decades of peace and American power from wholesale terror or even a mental outline of what that entails. But who knows how long that will last? When that protection fades, Europeans will feel betrayed by America and, more justifiably, by their own leaders for failing to prepare and defend them in a much more hostile and frightening world. Their leaders will likely come to rue not taking seriously Zelensky’s offer in his Victory Plan : a Ukrainian army stationed across Europe, for Europe’s defence, as America turns away from the continent. But by then, it will probably be too late.

Fundraiser

It isn’t too late now. My friends are still raising money to purchase the medical evacuation vehicle for wounded soldiers defending Kharkiv. Please donate if you can.