A Safe Haven on the Long Road to Victory

In recent weeks, the discussion of providing Ukraine with a ‘West German’ option for NATO membership has intensified. It has also become clear that everyone has their own variation on what this ‘West German’ option would mean. Naturally, therefore, so do I.

In May this year, I attended a symposium at the Nobel Institute in Oslo dedicated to the Russo-Ukrainian war. Honestly, I found the experience quite difficult at first. I had arrived from Kharkiv (via Poland, naturally) and I found it difficult to switch to the detatched academese required in such situations. This is why I will forever be grateful to Professor Mary Sarotte, whose paper and eloquent discussion of NATO membership variations - not only West Germany but also Norway - guided me out of my selfish emotional stupor and back to trying to find solutions.

The following strategy is the result of that initial conversation, and many many other conversations at the highest, most detached, levels of Western ministries to the most engaged soldiers fighting out east. The first iteration was finalised in June and distributed among private channels by the Centre for Grand Strategy, to whom I am very grateful for their support and encouragement and would especially like to thank Maeve Ryan, John Bew, and Andrew Ehrhardt.

The strategy is very far from ideal or perfect and it isn’t intended to be. It is my view on what is needed, what is possible and why. There is much to criticise but it was borne out of, and intended as, an effort at finding solutions, not just impossibilities.

There are other such strategies out there related to air defence zones. I know Jack Watling and Ed Arnold are working hard on such questions. Their strategies are almost inevitably better than mine. For a start, the technical questions involved in air defence are outside my expertise, although there are already people tasked with developing the technical accompaniment to this and other *political* strategies. That said, I am grateful to Toby Dickinson and Thomas Lawson for their feedback on what is possible and making sure the political suggestions are viable, if not simple, and to Sasha and Emma for their collaboration as they develop similar plans.

So, in conclusion, the below is my contribution to the discussion on how to get Ukraine back on the path to victory, because I believe that path is the only route to a safe future for the continent of Europe. And because I love Ukraine and I don’t want Ukrainian heroes’ sacrifices to have been in vain or to watch any more Ukrainians die. If there was a solution that stopped the killing, an option for genuine good-faith negotiations, that would be a different conversation. But there is not. And Russian occupation will not stop the killing of Ukrainians, only of Russians. And if they want to stop being killed, they can just go home.

DONATE TO PURCHASE A MEDICAL EVACUATION UNIT TO SAVE INJURED HEROES IN KHARKIV.

Ukraine: A Safe Haven on the Road to Victory

Key points

· Neither Russia nor Ukraine can achieve total military victory, and good-faith negotiations with Putin are unlikely. The West, as a collective, is unable or unwilling to provide Ukraine with what it needs to win. Yet the West, especially Europe, should not countenance the defeat of Ukraine, given the costs to its credibility, geopolitical standing, energy, economy, and sociopolitical cohesion.

· The war's current trajectory places unsustainable demands on Ukraine's society, armed forces, and economy, exacerbated by unstable Western politics, on which the country's survival depends. This untenable situation could lead to political and civil unrest with dire consequences for the war, regional security, and Ukraine’s allies, UK included.

· Without a strategy for ensuring a Ukrainian victory, NATO and Ukraine should negotiate a ‘Safe Haven’ strategy. This would designate Kyiv and western Ukraine as safe havens, inviting them into NATO. The U.K. is well-placed to champion this proposal, which builds upon some important historical precedents.

· To avoid escalation, the process towards NATO membership for part of Ukraine would begin by phasing in bilateral air-defence sanctuaries.

· The strategy would include long-term military, defensive, economic, and humanitarian commitments from NATO to Ukrainian territories outside the Safe Haven zone. An incremental, regional approach will facilitate Ukraine’s revitalisation and remilitarisation, as selected areas attract investment, rebuild, and grow economically.

· The strategy is underpinned by three aims:

o To provide sanctuary via air defence zones for at least parts of Ukraine’s economy, military production and society to revitalise

o To improve parity between the Russian and Ukrainian militaries by undoing Russian air superiority, allowing Ukraine to strike missile and other military sites inside Russia, and providing for resource reallocation from the west to the east.

o To bolster Ukrainian morale by providing a concrete path and evidence of progress via the sanctuaries and commitments within the strategy.

· The Safe Haven strategy is the worst option, except for all the others. It is a politically difficult but achievable option that delivers some concrete benefits for Ukraine while keeping the alliance united.

(1) The West lacks the political will needed for Ukraine’s victory. While European governments, Western analysts, and Ukrainian military figures have proposed several theoretically feasible victory strategies, the West lacks the political will to implement the necessary domestic spending and policies. Instead, there is a strained complacency, leaving Ukraine without adequate means to defend its people and territory. The Anders Fogh Rasmussen proposal of partial NATO membership for all non-occupied Ukraine was unworkable due to shifting borders and potential NATO-Russia conflict. The proposed ‘Safe Haven’ solution aims to address these issues, recognizing the urgent need for proactive defence in a country exhausted by over ten years of conflict and two years of full-scale war.

(2) The West, especially Europe, would suffer immensely from the defeat of Ukraine. The Russo-Ukraine war does not pose an immediate existential threat to NATO's security architecture, but a Ukrainian defeat would. A victorious Russia would likely test Article 5's robustness by staging a Donbas-like situation with semi-deniable military intervention in Russian-speaking areas around Daugavpils (Latvia) or Narva (Estonia). Defeat would force European countries, including the UK, to face significantly higher defence spending, food inflation, and energy costs, on top of an already fragile security situation and mass refugee flows. Given the West’s sunk costs, public support for Ukraine, and the ensuing humanitarian catastrophe, NATO countries are sufficiently committed to continue supporting Ukraine's survival but not enable its defeat of Russia.

Figure 1: Two maps, one year apart, showing the lack of significant progress by either side on the battlefield. Institute for the Study of War

(3) Russia is in a stronger position than Ukraine to sustain the war on its current trajectory (which this strategy aims to change). No side is currently capable of significant military advances, as shown in Figure 1. However, Russia has partially mobilized its economy for war, receives increasing support from China and other partners, and has vastly more manpower and economic resources. Russia is trying to stretch Ukrainian resources by opening a new front north of Kharkiv. While most Russians can ignore the war, Ukrainians cannot; they suffer more and are increasingly demoralized by fears that the deaths have been in vain, with no clear path to NATO membership or liberation to 1991 borders. Without hope, Ukraine's socio-political issues may lead to political unrest or further difficulty mobilizing soldiers, dramatically altering the war's dynamics.

(4) While Putin is in power, negotiations with Russia are unworkable. Negotiations are often framed as the West compelling Ukraine to renounce its 1991 borders,[4] but the main obstacle is that Ukraine has no negotiating partner. Russia is interested only in variations on Ukrainian capitulation. Putin has repeatedly stated unreasonable conditions to meet before even starting negotiations: Ukraine must withdraw its troops from four regions Russia claimed to annex two years ago, despite never fully controlling them. This would mean handing over millions of Ukrainians, including the never-occupied city of Zaporizhzhia, to Russian occupation, torture, and repression. Putin also demands that Ukraine commit to military neutrality, although this was enshrined in 2014 and Russia still invaded. However, Russia’s indifference to Finland and Sweden joining NATO highlights the real issue: not NATO itself, but Ukraine in NATO, as Putin sees Ukraine as part of Russia’s dominion.

(5) The only way to deter Russia is to prevent it from realising its ambitions to destroy Ukrainian sovereignty. Right now, the Kremlin believes it has more staying power than the West in Ukraine. A shift in the West’s policy to focus on sanctuary, parity and morale for Ukraine is essential to proving the Kremlin wrong. Russia’s somewhat advantageous position should not be overestimated: it stems largely from its determination and political will; it is suffering a number of deficits, is unwilling to undergo a new wave of mobilisation, and there are structural economic, infrastructural problems that will only worsen over time.

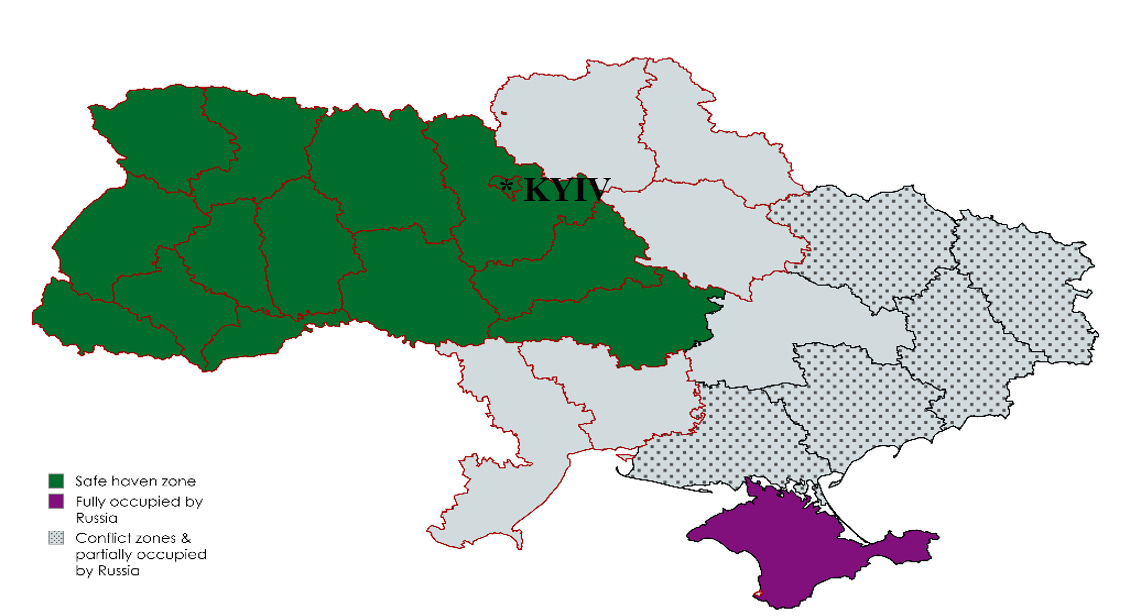

Figure 2. Proposed Borders for Ukraine Partial NATO Membership (Safe Haven Zone)

(6) ‘Safe Haven’ NATO membership for western Ukraine offers a way out of the impasse. Firm borders are a prerequisite for NATO membership, and Fig. 2 above suggests provisional borders that individual member states could commit to defending. The selection is based on three assumptions:

i. that certain individual member states would directly intervene to prevent the fall of Kyiv.

ii. that Ukraine and Russia will continue fighting in the conflict zones east of the Safe Haven zone.

iii. that NATO allies would not collectively agree to provide Article 5 guarantees to conflict zones or nearby regions.

The Safe Haven Strategy addresses President Zelensky’s criticisms of Anders Fogh Rasmussen's partial NATO membership plan, which proposed that Ukraine join NATO up to the points occupied by Russia. This plan would be untenable as it would draw shifting borders through villages and towns.

(7) NATO membership would only follow a phased introduction of bilateral air-defence sanctuaries. Although NATO would need to collectively pre-agree the outlines of the Safe Haven plan, the initial air-defence sanctuaries would be secured via bilateral agreements, with member states acting outside the NATO framework, using the Kyiv Security Compact as a bridge to NATO. The air-defence sanctuaries can function independently of the NATO accession discussion.

The suggested timeline of action is outlined below but would need to be flexible; for instance, under a Trump presidency, the distinctions of the air defence sanctuaries could be extended, particularly in the third phase. So too is flexibility required in terms of the exact area of the Air Defence Zones; it may be preferable to initially organise Air Defence Zones over specific areas of critical infrastructure rather than certain regions. As such, the below should be understood as a starting point for discussion:

Initial Preparation (1 month):

Agree on the Safe Haven strategy in principle among NATO members and provide a formal timeline for accession to Ukraine framed in terms of Safe Haven phases and Article 2 obligations rather than years.

Should it prove impossible to garner the required collective political will of NATO, the Safe Haven strategy could proceed with a coalition of the willing, namely bilateral partners of Ukraine willing to partake in policing air defence zones.

Organize bilateral air-defence sanctuaries, with the close involvement of Allied air forces to select zones to be protected and specifying the longitudinal and latitudinal lines to be protected, which may not align exactly with oblast boundaries.

Clarify that the air-defence sanctuaries are limited to air defence and do not cover other forms of protection, e.g. cyber warfare. Involved countries will also have to agree on responses in relation to a variety of scenarios.

Develop a strategy for areas outside the Safe Haven zone, including enabling Ukrainian soldiers to implement enhanced air defence against Shahed drones and cruise missiles in the east of the country. This will also include difficult limitations; for example, it will not be permissible to shoot down cruise or ballistic missiles and UAS outside of the agreed sanctuaries.

Create a clear messaging and counter-propaganda strategy ahead of the public announcement. This should underline two key points: 1) Safe Haven does not equate to NATO membership nor does it cover Article 5 guarantees; 2) Fighting will continue outside the Safe Haven and Ukraine’s allies will continue to support the UAF while the air defence sanctuaries plus policies in favour of military parity (e.g. lifting restrictions on Ukrainian strikes into Russia) will enable Ukraine to wage war in the east under more favourable conditions.

Phase 1: Western Border Sanctuary (1-3 months):

Figure 3. Safe Haven Phase 1. Border regions.

Establish an air defence sanctuary over the Western border regions. This allows Russia to test the boundaries without triggering Article 5. It may involve shooting down a Russian missile but is highly unlikely to involve shooting down a Russian fighter jet (although Turkey did shoot down a Russian Sukhoi Su-24 fighter jet and pilot without consequence in 2015). In the Safe Haven scenario, the situation would be analogous to the actions of the coalition of Western countries who shot down Iranian UAVs heading towards Israel.

Provide additional support to frontline regions against likely Russian escalation in response.

Phase 2: West Ukraine Sanctuary (3-5 months):

Figure 4. Safe Haven Phase 2 West Ukraine Sanctuary

Extend the air defence sanctuary up to, but not including Kyiv.

Ensure measures are in place to adapt to political changes, such as a potential Trump presidency, which may require adjustments. Have an agreed phase 6 to avoid fears of an east-west partition.

Figure 5. Safe Haven Phase 3 Kyiv

Establish air defence sanctuary covering Kyiv.

Announce phase 6, such as air defence sanctuary for critical infrastructure in the east, especially areas such as Mykolaiv or Chernihiv, Poltava, and Dnipro, depending on the war’s progression.

Clarify that the Safe Haven will extend to other territories (east of Kyiv) to prevent the degradation of those areas.

Phase 4: Critical Infrastructure Sanctuary in Southern Ukraine (8-12 months)

Figure 6. Safe Haven Phase 3 plus critical infrastructure in Odesa and Mykolayiv regions

· The fourth phase should include air defence zones over Yuzhnoukrainska Nuclear Power plant in Mykolayiv and the Ukrainian humanitarian sea corridor in Odesa.

· This would enhance nuclear security (with three of Ukraine’s four nuclear power plants under air defence) and economic revitalisation, as the sea ports of Odesa can contribute +8% to Ukraine’s GDP growth

· It also reassures Ukrainians that sanctuary is not limited to the Safe Haven zone (Kyiv+West Ukraine, aka Phase 3 territories), an assurance that will be bolstered by relocating Ukrainian air defence systems to the east and real defence-industrial cooperation between Ukraine and partners for the benefit of the front.

Phase 5: Kyiv + West Ukraine NATO Membership:

Begin formal talks of accession of the Safe Haven area (not including Odesa and Mykolayiv regions) of Ukraine into NATO, provided Ukraine has satisfied the metrics relating to Article 2.

Maintain flexibility in the timeline and scope of the air defence sanctuaries and NATO integration based on evolving circumstances, emphasizing that the eastern regions are not excluded from the Safe Haven strategy but simply on a different timeline for NATO membership compared to West Ukraine and Kyiv.

(8) Staggered implementation balances deterrence and restraint to maintain NATO unity. The current Safe Haven strategy timeline covers the next two years by which point contact lines, resembling an expanded version of the Donbas conflict after 2015, will likely have been established. While active fighting continues in the east, Western governments won't support NATO membership for surrounding regions. However, the Safe Haven strategy reassures Ukrainians that their sacrifices are meaningful, affirming their choice to align with the West. Clear messaging will emphasize that the strategy is for all of Ukraine and will extend to more regions when feasible. The initial bilateral air defence sanctuaries stagger and prepare for Ukraine's NATO accession and manage Russia’s response in a de-escalatory manner.

(9) Russia would not be party to, or able to spoil, negotiations. A staggered implementation period reduces the escalatory nature of the proposed Safe Haven strategy without yielding to Russia’s genocidal whims. The strategy will be negotiated between Ukraine and NATO, preventing Russia from playing a spoiler role. Additionally, parts of the strategy could be ‘sold’ to the Russians: the initial focus on western Ukraine reflects military realities and the fact that Russia does not claim the same baseless historical ownership over that region. Russian politicians have previously suggested partitioning Ukraine and may choose to present it that way to domestic audiences, although this would be inaccurate.

(10) The Safe Haven strategy affirms Ukrainian sacrifices by offering concrete progress in the form of air defence sanctuaries and NATO membership for parts of Ukraine. The proposal should evolve and extend with implementation and the war; for example, additional phases involving air defence sanctuaries for critical infrastructure beyond Odesa and Mykolayiv. The strategy’s flexibility also means the timeline and scope of the air defence sanctuaries and NATO integration can be adapted based on developments on the ground.

(11) Ukraine traditionally has a strong society and weak institutions. By focussing on Article 2 of the NATO Charter, the Safe Haven strategy ensures institution strengthening becomes an integral part of the country’s NATO accession. As demonstrated by ‘Article IV: Institutional Reforms to Advance Euro–Atlantic Integration’ of the US-Ukraine Bilateral Security Agreement, some Western partners still have concerns relating to the strength, accountability and transparency of the judiciary, military, law enforcement, tax and customs agencies, and anti-corruption bodies. Regardless of whether these concerns are exaggerated or fair, making Ukraine’s accession to NATO conditional on implementing these reforms will strengthen Ukraine’s democracy and bolster morale while also allaying fears and reservations among some NATO allies.

(12) An incremental and regional approach allows for Ukraine’s revitalisation and remilitarisation. The Safe Haven strategy will enable selected areas to attract investment, rebuild, and grow economically. Combined with the reforms mentioned in point 10, the provision of air defence sanctuaries will provide scope for economic growth that will help fund the fighting in eastern regions, accelerate technological innovation, train soldiers safely, and increase weapons production. With enhanced commitments from NATO member states—such as additional air defence, fighter jets, and economic and humanitarian aid—eastern Ukraine will be stronger than it would be without the Safe Haven proposal, though not as strong as the western regions

Figure 6. Graffiti in Kharkiv asking “Where is our Lendlease?” March 2024. Author's Photo

(13) This strategy avoids legitimizing Russian control. The horror of Russian occupation and Ukrainians' fierce resistance make the most unsettling aspect of this strategy its potential perception as legitimizing Russian aggression or accepting Russian dominion over currently occupied territories. These territories will remain under de facto control but not be recognized as Russian. Moreover, this strategy allows Ukraine to focus its military efforts on preventing further areas from falling under occupation or being destroyed, as seen with Chasiv Yar, Avdiivka, and Vovchansk in 2024. Since other, free, Ukrainian regions will also fall outside the Kyiv + West partial NATO membership, the Safe Haven strategy should be understood as an ongoing process rather than an admission of partition. This stance will be more credible with commitments from Ukraine and bilateral partners to support resistance in the occupied territories.

(14) Ukraine in NATO will enhance European security. This proposal is more than a recognition of Ukrainian military skill, ingenuity, and resilience; Ukraine will also bring many benefits to the rest of Europe through their fighting experience, expertise, and knowledge sharing. Access to these will enhance European defence at a critical time, when the USA is demanding the continent take more responsibility for its own security. Moreover, without offering concrete progress to Ukraine, the West risks losing Ukraine’s loyalty and its own credibility, as NATO has reaffirmed repeatedly that Ukraine’s future is in NATO. Gradual Ukrainian accession along a clear path is a means for NATO countries to influence Ukrainian politics.

(15) There are historical precedents for bespoke NATO membership. When Norway joined NATO in 1949, it also shared a direct border with Russia (then the Soviet Union) and imposed self-restrictions: no foreign troops during peacetime, no military exercises near the border, and no deployment of atomic weapons. By joining NATO but refusing NATO infrastructure, Norway's strategy offered a flexible model for balancing deterrence and restraint. As Mary Sarotte has argued, these historical precedents could be adapted for Ukraine. While Ukraine may not be concerned about angering Moscow, such agreements could reassure NATO allies more inclined toward restraint.

(16) Provisional borders are not irrevocable: the ultimate aim is NATO membership for Ukraine in 1991 borders. As Mary Sarotte also points out, despite being divided into East and West, West Germany joined NATO in 1955, with its membership designed to accommodate but not legally recognize the realities of partition. This involved establishing provisional borders that were clear and defensible while upholding the goal of eventual reunification. As West Germany demonstrated, these provisional borders were not irrevocable. The eastern regions of Ukraine are in a much stronger position than East Germany was, which can be reflected in bespoke measures within the Safe Haven strategy. This approach signals the ultimate goal for all of Ukraine to eventually join NATO, providing concrete steps towards this with tangible security benefits for war-torn areas, such as enhanced air defence to protect from cruise missile and Shahed drone attacks.

(17) Russian escalation will likely occur outside the NATO zone and should be mitigated. One reason for the West's hesitancy to support Ukraine is the fear of a Russia-NATO war leading to nuclear weapons usage. However, Russian drones and missiles breaching NATO airspace are already leading to risks of escalation; this strategy ensures that Russian missiles are shot down over Ukrainian territory. Moreover, Russia's nuclear blackmail could result in large-scale nuclear proliferation if Ukraine is defeated. Any country threatened by a nuclear neighbour would seek to acquire nuclear weapons, increasing proliferation and risk. Moreover, Russian threats and red lines have been consistently crossed by NATO states with little consequence, beyond more bombardment of eastern Ukraine. A similar response should be expected towards the Safe Haven strategy and mitigated by providing enhanced support, such as air defences, fighter jets, and economic and humanitarian aid. This will also help reduce internal division and mass emigration from those regions.

(18) The Safe Haven strategy is not a sudden innovation; it builds on existing functioning security partnerships and bilateral agreements within the Kyiv Security Compact, Rasmussen’s proposals, and ongoing discussions among NATO members about air defence sanctuaries. Additionally, Rasmussen's introduction of partial NATO membership into public discourse has already garnered some Ukrainian public familiarity and support. A 2023 survey of "hybrid" security guarantees showed "joining NATO partially" had the most supporters. If elected, Trump might attempt a peace deal with Russia, but it is unlikely to succeed given it does not meet Russia's pre-negotiating conditions. Considering the turbulent political landscape within and across NATO states, a strong mediator and promoter of the Safe Haven strategy at the national level is essential.

(19) The UK is ideally positioned to champion the Safe Haven strategy within NATO. An

incoming UK government could restore the UK's historical role as a bridge between Europe and the US. The current division within NATO—between US and German restraint and the more interventionist stances of Eastern European, Baltic, and Scandinavian countries—has strained NATO unity. Labour's close ties to Biden and Germany’s SDP, along with its policy alignment on Ukraine with Eastern European, Baltic, and Nordic countries, position it well for this role. Additionally, the UK's leading support for Ukraine’s self-defence has earned it significant respect and trust in Kyiv. This trust, combined with the UK being untainted by the Minsk agreements (unlike France), uniquely positions it to promote the Safe Haven strategy to Ukraine.

(20) The Safe Haven strategy is the worst option, except for all the others. The Safe Haven strategy is flawed and deeply unfair: Ukraine deserves all its territory back and for its people to live in peace. Ideally, the West would provide Ukraine with everything it needs to defeat Russia and dismantle its ideology, ultimately benefiting Russia as well. However, this is politically unlikely. The Safe Haven strategy has one benefit: it is a politically difficult but achievable option that delivers some concrete benefits for Ukraine while keeping the alliance united. Given the lack of workable alternatives and the potential for the war to worsen both Ukraine’s and the West’s security and prosperity, the Safe Haven strategy offers hope. It acknowledges that Western commitments to Ukraine are not those of the Good Samaritan but of a neighbour who helps put out a fire before it spreads to their own home.

DONATE TO PURCHASE A MEDICAL EVACUATION UNIT TO SAVE INJURED HEROES IN KHARKIV.